The Unreality of Sin

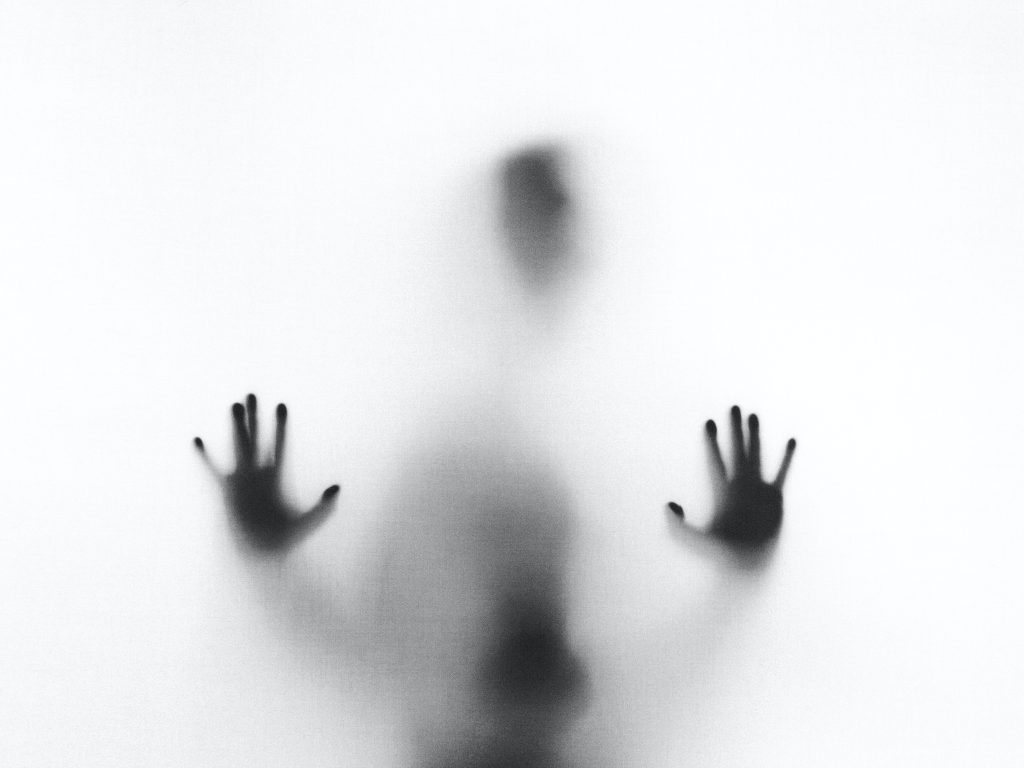

Authors in the Great Tradition describe sin as becoming less real and losing our humanity–we see this happening all around us.

One of the blessings of teaching humanities classes at different levels that cover different time periods is seeing the connections between the various texts in the Great Tradition. Students can see how ideas are born, grow, and develop. One reason for this is because we are reading the books that the classic writers themselves read. Through this process, we enter the Great Conversation. I noticed this recently while teaching an Integrated Humanities course for high school students. The course covers the Medieval period through the Reformation.

We begin the class with selections from Augustine’s City of God. Augustine wrote his classic work in 410, in response to the Gothic invasion of Rome. It was the first time Rome had fallen to a foreign foe in 800 years, and many blamed the Christians for leading the Romans away from worshiping their ancestral gods. Augustine’s purpose in this magisterial work is to defend the “City of God” from its pagan detractors. Throughout, he contrasts the eternal City of God from the earthly City of Man (typified by Rome). The City of God is characterized by love, humility, and the worship of the true God, while the City of Man is marked by pride, war, and spiritual bondage to demons. While discussing the nature of sin, Augustine makes a penetrating comment. He is meditating on what happened to Adam and Eve when they ate the forbidden fruit. When they disobeyed God, they did not immediately die or disintegrate–they became “less real.”

“Yet man did not fall away to the extent of losing all being; but when he had turned towards himself his being was less real than when he adhered to him who exists in a supreme degree. And so, to abandon God and to exist in oneself, that is to please oneself, is not immediately to lose all being; but it is to come nearer to nothingness” (Penguin Classics, Book XIV, chap. 13).

Now, there is more than a little of Neoplatonic metaphysics behind this formulation, and it is not my goal to defend that framework in its entirety. However, I believe Augustine has a valuable insight here, one that we can apply without adopting his Neoplatonism. Adam’s sin here was trying to be self-sufficient, trying to exist free from God’s command. By asserting his own will, his will became perverted, distorted, and twisted. By endeavoring to exist apart from God’s will, he began to diminish, and to lose the fullness of life and existence that God had planned for him. As Augustine explains further in the same section: “This then is the original evil: man regards himself as his own light, and turns away from that light which would make man himself a light if he would set his heart on it.”

In class, I compared this idea to the Black Riders in The Lord of the Rings. Formerly kings and men, the ring-wraiths are shadows, pale imitations of their former selves, totally bound and enslaved by the power of the one ring and its evil master. They have lost the ability of self-determination; they have lost fullness of life and being.

The next book we read in my class is Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy. Boethius was a highly educated civil servant in the decaying Western Roman empire ruled by the Ostrogoths. Boethius wrote his influential Consolation while in prison, having fallen from the Ostrogothic king’s favor because of various political intrigues, and he wrote it about a century after Austine’s City of God. Boethius was copiously well-read in classics, and so it is possible that he had read Augustine. Whether drawing from Augustine or another source they both read, Boethius makes the same basic points about the “unreality of sin”.

In this center-piece of Western thought, Lady Philosophy visits Boethius in his cell to remind him of the truths that he forgot, and to help him consider his fall from grace from the perspective of God’s providence and the ever-turning wheel of Fortune. The book is a treasury of early Medieval thought. At one point, Boethius and Philosophy are discussing the differences between good and bad men. After establishing that all men seek “happiness” or the “good” (however they define it), Philosophy states that those who turn away from seeking the true good to pursue pleasure or vice begin to lose their fullness of existence:

“And if you say they abandon goodness and turn to vice knowingly and willingly, this way they not only cease to be powerful, but cease to be at all. Men who give up the common goal of all things that exist, thereby cease to exist themselves … I am not trying to deny the wickedness of the wicked; what I do deny is that their existence is absolute and complete existence. Just as you might call a corpse a dead man, but couldn’t simply call it a man, so I would agree that the wicked are wicked, but could not agree that they have unqualified existence. A thing exists when it keeps its proper place and preserves its own nature. Anything which departs from this ceases to exist, because its existence depends on the preservation of its nature” (Penguin Classics, IV.2)

Engaging in a bit of Neoplatonic metaphysical speculation, Lady Philosophy further explains the “unreality of sin”:

“A short while ago you learned that all that exists is in a state of unity and that goodness itself is a unity; from which it follows that we must see everything that exists as good. This means that anything which turns away from goodness ceases to exist, and thus that the wicked cease to be what they once were. That they used to be human is shown by the human appearance of their body which still remains. So it was by falling into wickedness that they also lost their human nature” (4.3).

Lady Philosophy then details how we describe wicked people with animal characteristics. But this is not just a relic of classical philosophy. The Bible also speaks like this.

Romans 1:18-32 describes the downward spiral of spin and what happens to people when they turn away from the true God. Because they refused to honor or thank the God known to them through natural, they “became futile in their thinking, and their foolish hearts were darkened,” and they “exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling mortal man and birds and animals and creeping things” (Ro. 1:21, 23). Since they worshiped beasts, God gave them over to beastly desires and impulses: “Therefore God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the dishonoring of their bodies among themselves” (Ro. 1:24-25). Sexual perversion and immorality of all kinds follows in the wake of this primordial exchange. We exchanged our God-given natures, made in the image of God, made to reflect his glory and goodness, and we wallowed in shadowy muck and mud of sin. We thought it was real life, real freedom, but it was really slavery. We thought sin would make us more like God–the ancient lie heard first in the Garden–but it hurled us out of Eden, into the realm of unreality. We lost our original connection to Ultimate Reality, and have been trying to fashion our own distorted and twisted models of reality ever since.

2 Peter 2:1-22 also describes the true “Descent of Man”: “But these, like irrational animals, creatures of instinct, born to be caught and destroyed” (v. 12; cf. Jude 10-11); “They promise them freedom, but they themselves are slaves of corruption. For whatever overcomes a person, to that he is enslaved” (v. 19). Sin makes us less real–less human. It distorts, perverts, and assaults our original nature.

Jumping ahead a few hundred years, we see this same theme in Milton’s Paradise Lost. In Book XI.515-525 the Archangel Michael describes the effects of the Fall to Adam in a vision of the future:

Thir Maker’s Image, answer’d Michael, then

Forsook them, when themselves they vilifi’d

To serve ungovern’d appetite, and took

His Image whom they served, a brutish vice,

Inductive mainly to the sin of Eve.

Therefore so abject is their punishment,

Disfiguring not God’s likeness, but their own,

Or if his likeness, by themselves, defaced

While they pervert pure Nature’s healthful rules

To loathsome sickness, worthily, since they

God’s Image did not reverence in themselves.

The unreality of sin also shows up in a more recent classic–C.S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce. The “ghosts” who are allowed a brief holiday from Hell are initially shocked at the bright intensity and hardness of the outer regions of heaven. They are told that it will not last, and they will learn to tolerate the hardness of heaven. The implication is that sin has made them less real, insubstantial, and ghostly in hell. Encountering the pure intensity of holiness, and through giving up their besetting sins, they can become more real. In fact, the spirits from heaven who come to visit and help the tourist ghosts from hell are described as the “solid people.”

But studying the classics should never remain a time-traveling spectator sport. We must always apply the insights of the past to help us understand and live wisely in our present. And this is where the insight about the “unreality of sin” really helps us. Our culture is fragmenting exponentially, as we draw out the last reserves from our cultural heritage of Christianity. When people are filled with pride, when they turn away from the only source of existence, life, joy, and purpose, they increasingly lose their humanity.

We see this on a basic level as people mark their bodies with excessive tattoos, unsightly piercings, rainbow hair dying, and black make-up. More seriously, people search for, and experiment with, their sexual identity, unmoored from the body God gave them. Our humanity is no longer fixed or certain–all is in flux, up for grabs, and open to personal “identification.” Bodies are mutilated in the quest for sexual wholeness–torn open, cut, manipulated, and scarred for life in a vain quest for healing. We have literally lost our humanity. Slaves of our lusts, confused and wandering, wraith-like in our addictions.

As if that were not enough, others seriously advocate transhumanism, seeking to transform and alter and improve our human bodies through technology. There are no limits to these Frankenstein imaginings. Others call for virtual reality for everyone, so we can transcend our boring and mundane human lives in the real world. Still others embrace their loss of humanity and identify as “Furries,” dressing up as animals and cavorting in dog parks together. A Japanese man recently spent $14,000 on a realistic collie costume because he felt he had always been an animal deep down somewhere in the “real” recesses of his being.

In all of these attempts to build another Tower of Babel, the common theme is the loss of our human reality. Whether it is broken and twisted through chemical dependency, altered or manipulated through surgery, or left behind in a virtual dream-scape, we are becoming less real by the minute.

What is the way out of this “unreality”? Both the Bible and the Great Tradition answer: Humility! Augustine focuses on humility as the only antidote to the pride that dominates the City of Man (City of God, XIV.13). Humility reminds us of our true nature as beings created by, and dependent on, God. Humility submits to God’s design for humanity, which is the only path to true freedom, and to true reality.

Boethius, on the other hand, argues that we must become “divine.” This sounds suspicious to moderns, but this is an ancient way of thinking. Boethius means that we must participate in God’s original goodness (Consolation, III.10, IV.3). We don’t have to accept the framework of neo-Platonism to benefit from Boethius’s main point. Speaking this way echoes one of the ways that the Bible speaks of salvation.

2 Peter 1:3-4 teaches us: “His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of him who called us to his own glory and excellence, by which he granted to us his precious and very great promises, so that through them you may become partakers of the divine nature, having escaped from the corruption that is in the world because of sinful nature” (emphasis added).

The Eastern Christian church has preserved this insight in its doctrine of theosis. To simplify terribly, Orthodox theologians have focused more on how union with Christ progressively transforms us more and more into the image of God, which was defaced by sin. In Protestant terms, this is the process of “sanctification,” becoming more and more holy throughout our lives. It is the process of liberation from the realm of the Unreal, from the lies and slavery of sin: “The good man, though a slave, is free; the wicked, though he reigns, is a slave, and not the slave of a single man, but–what is far worse–the slave of as many masters as he has vices” (Augustine, City of God, Bk. 4.3).

As a more recent theologian puts it: “God knows that he is the ultimate being, that there are in reality none to compare with him. In calling upon people to turn from idols, therefore, God in no way is asking something of us not in accord with reality. In steadfastly opposing idolatry he seeks to protect people from ultimate concerns destined to disillusion and disappoint. God desires our worship for our sakes, that we not succumb eventually to despair as one after another of our finite gods lets us down.” (G.R. Lewis, “God, Attributes of,” Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, 457).

Through faith in Christ, in union with him, we have been transformed. We are on a journey towards Ultimate Reality. We don’t know exactly what that will look like, but we know we will be like Jesus, the truly Real Man (1 John 3:2). This hope helps us to fight against the downward pull towards unreality (1 John 3:3). As we journey through this realm of fragmentation and shadows, and as our original nature is restored more and more, we look forward to Ultimate Joy in the presence of Ultimate Reality, for eternity: “You make known to me the path of life; in your presence there is fullness of joy; at your right hand are pleasures forevermore” (Ps. 16:11).

Gregory Soderberg Ph.D., teaches and mentors students of all ages at Kepler Education, the BibleMesh Institute, and Redemption Seminary. He writes at gregorysoderberg.substack.com.

Wow, Greg. Just wow. This article has evoked so many images and thoughts for me. From Lewis’ The Great Divorce, “The light, like solid blocks, intolerable of edge and weight, came thundering upon my head,” to memories of Tolkien’s ghost armies, even to Zelazny’s Amber, all of these echo the perspective that the real world, the more ‘solid’ world, is out there. And moreover, is Satan’s chief aim to uncreate? To unmake what God has made? You’ve left me with much to ponder. Thank you, brother.