“Out of all the sciences above named, however, the ancients, in their studies, especially selected seven to be mastered by those who were to be educated. These seven they considered so to excel all the rest in usefulness that anyone who had been thoroughly schooled in them might afterward come to a knowledge of the others by his own inquiry and effort rather than by listening to a teacher. For these, one might say, constitute the best instruments, the best rudiments, by which the way is prepared for the mind’s complete knowledge of philosophic truth. Therefore they are called by the name trivium and quadrivium, because by them, as by certain ways (viae), a quick mind enters into the secret places of wisdom.”

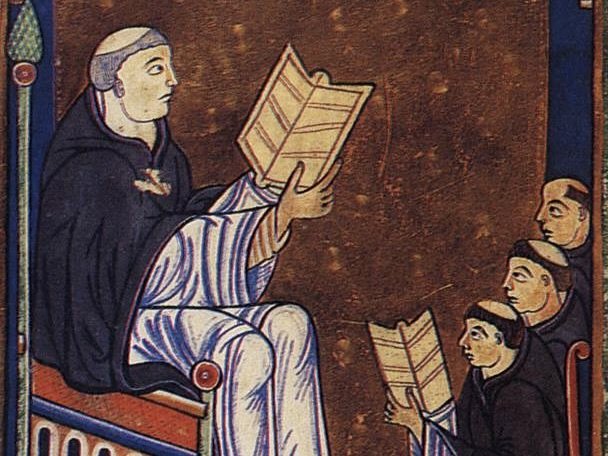

This is one of the many jewels in Hugh of St. Victor’s Didascalicon: De studio legendi (On the Study of Reading), a twelfth-century work on theology and the liberal arts that marks a true high point in medieval thought. Hugh (1096-1141) drew on the vast resources of the ancient world and his Christian fathers in the faith as he discussed the various divisions of human knowledge. His work reads like a card catalogue,and while his categories are a bit Platonic, his tome stands as a testimony to the immense learning and theo-centricity that characterized the medieval age.

The Didascalicon does not address educational theory or pedagogy as we think of the terms. His work is a map to guide the earnest student on an ever-ascending path up to conformity to the divine likeness: “This, then, is what the arts are concerned with, this is what they intend, namely, to restore within us the divine likeness.”

The observant reader will have noticed an echo of Dorothy Sayers in the first-quoted passage (or rather a voice Sayers was echoing): “For the sole end [of education] is simply this: to teach men how to learn for themselves; and whatever instruction fails to do this is effort spent in vain.”

It is unfortunate that Sayers did not footnote her classic essay. Perhaps she had this very passage from Hugh in mind. Then again, perhaps it is best that Sayers left us to dig through the thick layers of medieval thought for ourselves. I wish to play the role of a miner in this foray into the Didascalicon. Sometimes it feels that we in the Christian classical movement are all tunneling along through forgotten corridors and deserted halls. And so, I have dug up Hugh of St. Victor and hold him up to the light for all to see. He does have some blemishes, indeed some cracks, but the light still dances splendidly in his words.

As I turn the Didascalicon over in my hands, polishing here and marveling there, I will be simultaneously appreciating and appropriating. I struggled with both of these terms in choosing my title, but I feel that “appropriation” is the more biblical, and the most medieval, of the two. If something is worth appropriating, then it is first worth appreciating. And as Hugh appropriated Quintilian, Plato, Cassiodorus, and Boethius, I will appropriate him from a Protestant perspective, and endeavor to draw conclusions that would shed a little more light in this particular corridor of the medieval world. I hope that my mining will specifically benefit those involved in the revival of Classical Christian education.

[Read the rest at the Beza Institute for Reformed Classical Education …]

Dr. Gregory Soderberg is the Student Life Coordinator at Kepler Educationn and teaches Old Western Culture and Rhetoric classes. He writes at The SoderBlurb and has contributed to Common Good, SALVO, Touchstone, and American Reformer.